Olga Hohmann

Please Mind the Gap

Sophia Eisenhut and Max Eulitz Das Boot at Good Weather, Chicago x Scherben, Berlin

Some time ago, I was at the hardware store with an artist friend. It was a Tuesday afternoon and we were almost the only people in the rows –– and he remarked on what was obvious: namely that it is a special privilege of the artistic profession that you don't have to think of time in normative terms, i.e. that you can go to the hardware store on a Tuesday afternoon, do your shopping on a Wednesday night at eleven and work on Sundays.

It was a thought that stuck with me, not only because it meant finding empty supermarkets or hardware stores (a hot tip), but also because it gave me some insight into the work of that artist: it was Max Eulitz.

Max Eulitz' works are located in an intermediate space: the gap between the normative and the transgressive. Between the desire for accessibility and the pause, the hesitation. Between the fascination for anarchy and the desire to understand and be understood. Between a love of art and discomfort with the hermeticism of the so-called "art world". And between the attempt to crack the nut, that is, to understand the whole, the so-called system, and the devotion to detail and intimate narratives.

In Max Eulitz's new video work "Das Boot", which he realized together with Sophia Eisenhut, this gap is particularly apparent –– it is comparable to the gap between the boat and the mainland. And, before you get on or off the boat that this cinematic work represents, a voice so generic that it seems familiar, politely tells you: "Please mind the gap".

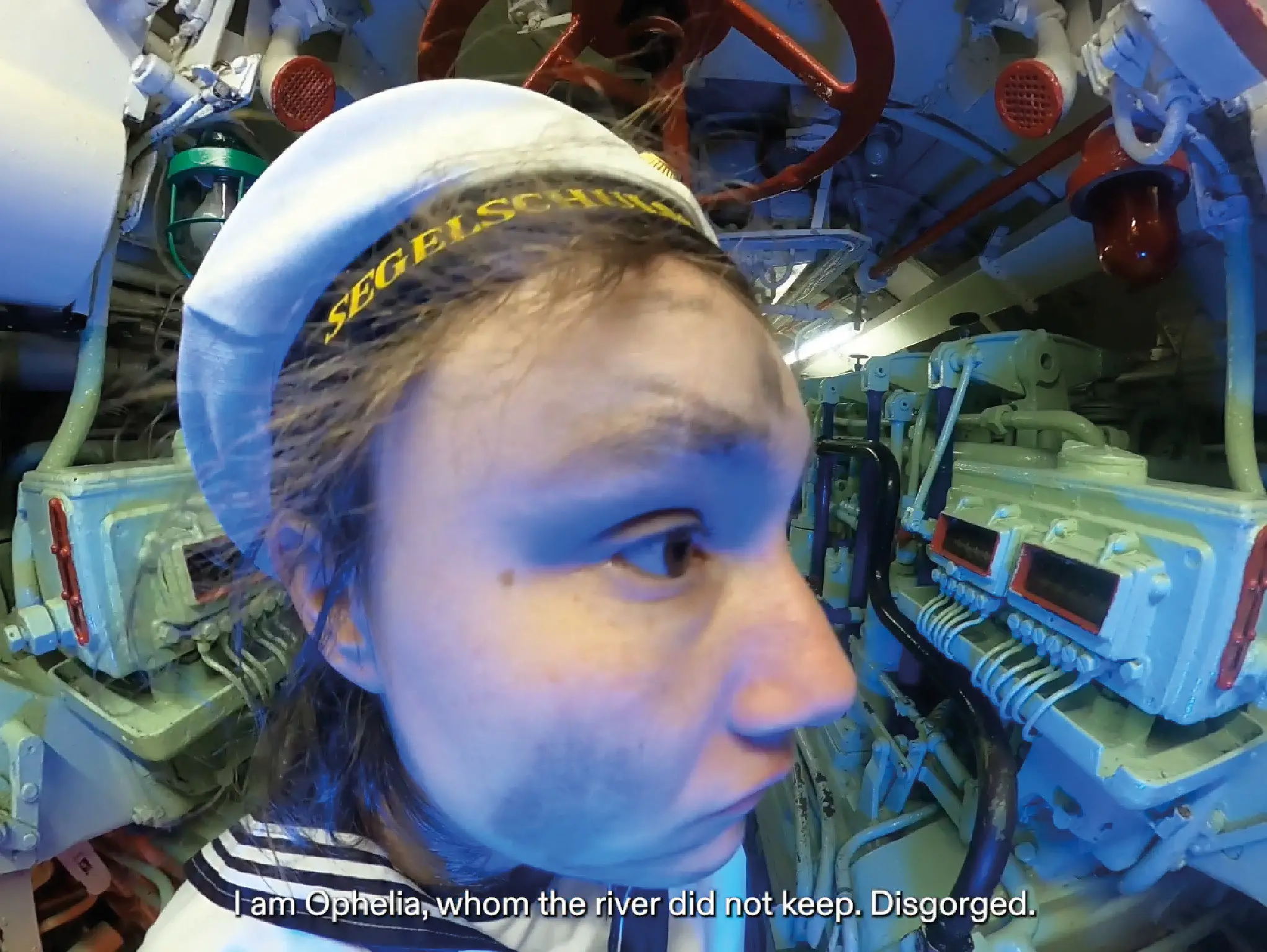

I learn that sailors sway on the mainland when they return after a long time at sea. A similar uncertainty on familiar ground also arises when we look at the work of Sophia Eisenhut and Max Eulitz: Nothing seems self-evident in the submarine, nothing seems to provide stability. The still unexplained fate of Jenny Böken, the cadet who died for reasons that are still unknown, is the subject of the work, which at first glance seems less socially critical than surreal. It is only the monthly cycle (her period) to which she must surrender and submit, that allows the protagonist to relinquish control from time to time. Otherwise, it is really only the "system" of daily life in the submarine that she has to submit to in the sense of a larger mission –– just as she finds herself, underwater, in a certain degree of self-sufficiency.

A work of art is also a kind of ship that repeatedly arrives and departs from different ports, that carries a cargo that can be more or less easily conveyed to the site-specific public and that releases swaying sailors who have spent a lot of time alone before being exposed to the public (the artist). Not only alone –– but also underwater.

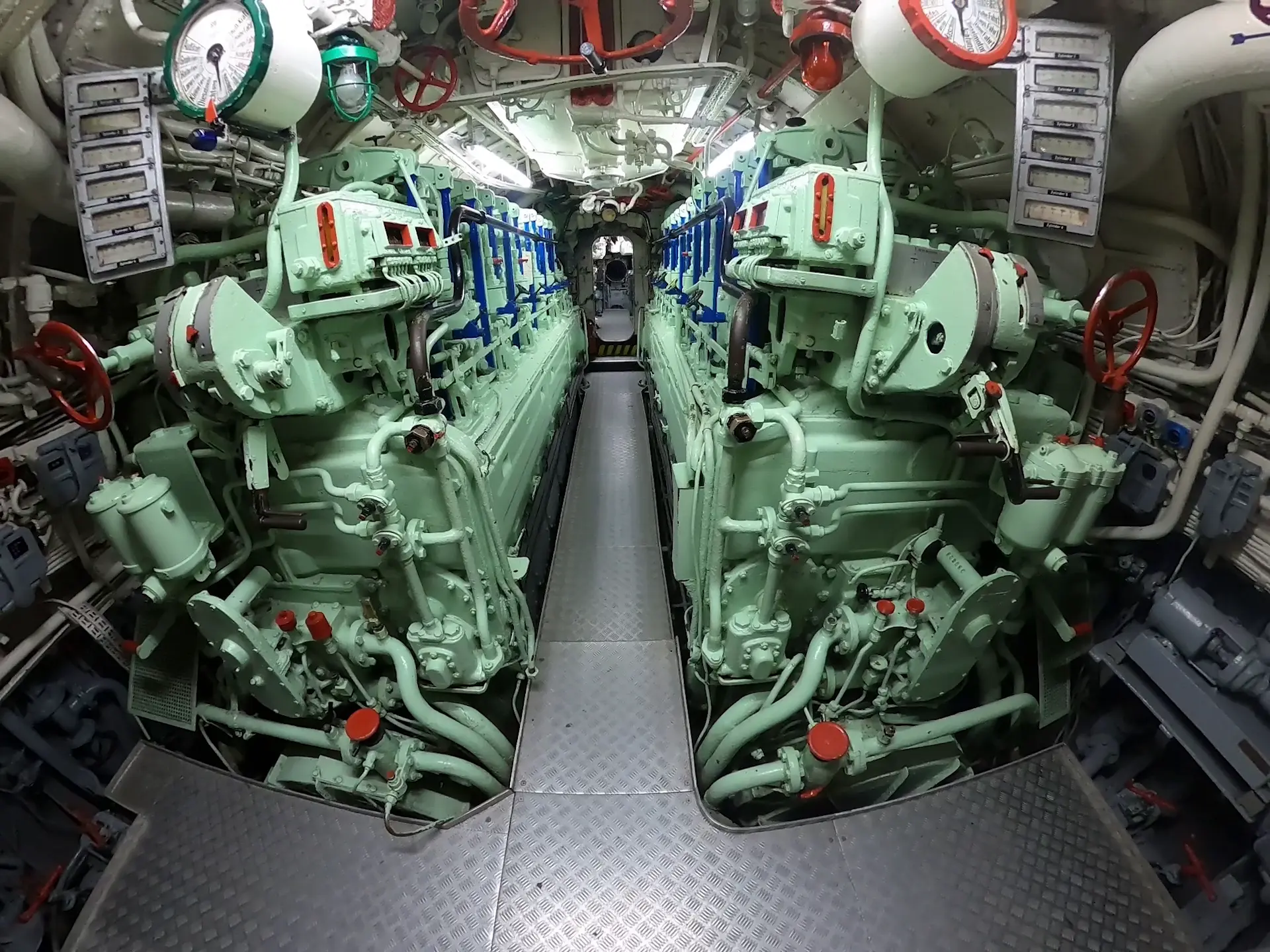

Underwater the senses function differently. You hear things muffled, distorted –– and only see the "normal world" through the periscope. The individual sees only ever a single section –– and precisely the one on which you consciously focus. Every observation is a decision, none of the observations are self-evident. Artists are those who look closely –– but this also means that they consciously look away from time to time. The periscope creates both a of claustrophobia, but also a liberating limitation.

In a way, it is perhaps as if we, as artists, were traveling on a boat and repeatedly docking at different ports to present our work. We are somewhat aware of the cargo of our ship, but we don't know exactly how it will be received because we don't know the respective codes of the countries. We do know those of the logistics companies, which are similar regardless of culture, though –– the so-called "art world".

In this equation, art institutes are of course the ports, the logistics companies –– and the audience is either the employees of those logistics companies or, depending on the artist, it is also the locals of the respective place who, depending on the information available, sometimes manage to book a tour and visit the ship –– or not.

But what is the "work" here, what is the practice and what is the attempt at mediation? You could say that the daily practice is the ship. And the most important part of the work for artists is to be alone on the sea (of possibilities). In this equation, the transported goods would then be the work. And the attempt at mediation is in the hands of the officers and sailors.

But you could also say that the ship itself is the work. And the practice consists of keeping it running, like one's own body. The sailor cannot be separated from her vessel and her way of operating it, of managing it (both economically and hygienically) is directly inscribed in it. And then there is the level of representation: Jenny Böken is traveling as an officer in the name of a country, as is an artist under certain circumstances.

As an artist, you can determine the logistics, the circumstances and, so to speak, the parameters, the conventions of your own work –– at least that's the myth.

"Das Boot" deals with aesthetics of body horror –– the inside of the submarine is compared with the inside of the body, which is plagued by cramps, or rather this connection is made as if by itself. Because your own body is as alien to you as if you were looking at it through a periscope with fish-eye optics. It only ever presents itself through instruments such as MRI scanners or x-ray machines.

"You only have a face if the public gives you one and you can't choose which one it is," says the protagonist, portrayed by Sophia Eisenhut in a mixture of reenactment, embodiment and self-portrait. Although it is applied here to her role as an officer in the German Navy, it is also a statement that can be applied to the role of the artist. Because: An artistic work is usually directed towards an outside –– and the anticipation of this exposure is part of the work. It is also another part of the work to anticipate who you could be in or in front of this external world, the audience, to shape and determine your face –– and how much you want to keep this face under control: Is it contouring or is it no-makeup-makeup?

In "The Boat", Sophia Eisenhut, or the role that she is playing, states that it would be "wondrous to still be alive". And you see her looking around, in the "normal world" on land, as if she doesn't know whether she has just been swallowed up by the whale (like Jonah) or, after such a long time in the stomach of the wale, that she could remember the "real world", spat out again. Sometimes, the studio feels like a womb, too.

It is only the monthly cycle that connects the sailors/artists with the people up on the mainland –– otherwise the self-evident things "from above" are blurred by the bubbling "below". Only the small section that can be seen through the periscope can be seen –– no turn, no twist is intuitive on its own, it is always mediated by the slow technology that follows the body –– just as the body in the lonely submarine follows the technology in everyday life.

After all, to what extent is an artist part of so-called "society"? And to what extent do the unspoken norms become particulary apparent (in you) when you try to evade them?

Spending your life underwater is a decision. It's a decision that artists/matros have made once and regretted many times –– but once you've decided to see the world from the distance of the peephole, you can't go back.

So it is also a decision for loneliness. And for alliance with the very few other people who took this very decision. Support between artists has always been a big part of practices. No work is created in a vacuum. And you have to consciously decide which company you surround yourself with.

Maybe that's why the title of the exhibition in the Chicago-based gallery "Good Weather" is Nemo, which (at least for millennials) immediately brings to mind Finding Nemo, but is also Latin for "nobody". It's a bit like the German joke in which a gentleman named "Doof" (let’s call him "Simpleton") complains to the police: "Niemand hat mir auf den Kopf gespuckt und Keiner hat’s gesehen" ("No-one spat on my head and nobody saw it"). But who is spitting on whose head here?

"Please Mind the Gap" says the voice from the off in the New York subway politely, it is so generic that it seems familiar. And Max Eulitz goes to the hardware store on a Tuesday afternoon to install a fixture for his video work "Das Boot", which he produced together with Sophia Eisenhut. He is not oblivious to the fact that he is in a void –– he is acutely aware of his special position. He actively appreciates that it is a Tuesday when he can go to the hardware store and not a Saturday. He looks at the "ordinary world" through his distorted periscope and actively rejoices in having to participate in it, only peripherally, only mediated. The norm is broken and questioned –– but in conscious demarcation, in regulated transgression, not in pure anarchy.

Even though there is a gap in the work of Sophia Eisenhut and Max Eulitz, it doesn’t necessarily mean that something is missing. It is difficult to pinpoint what it is that is absent –– but the viewer is oddly unsettled. Perhaps it is the half-fulfilled convention of seeing that meets with resistance, the more or less voluntary withdrawal.

It's a bit like looking into a distorted mirror in a slightly compulsive gesture of control to make sure that you are still "there" –– that the image you have of yourself still corresponds to the truth of "the spectators". It remains wondrous to be alive, inside and outside the whale’s stomach, which can feel like a womb sometimes.