Interview with Brett Seiler

"Doing the Most"

Before the interview in Leipzig, Brett Seiler took a nap on the sofa. "I think I have a migraine", says the South African-born artist with a smile, ruffling his hair. The 29-year-old, who has only been in Germany for a few months, is currently working on exhibitions in New York, London and Cologne from a small, paint-splattered "artist‘s flat" in Leipzig-Plagwitz.

I've always wondered, Brett, is there a reason why the people you paint don't have tattoos when you have so many?

They have no fingernails either (laughs).

They don't?

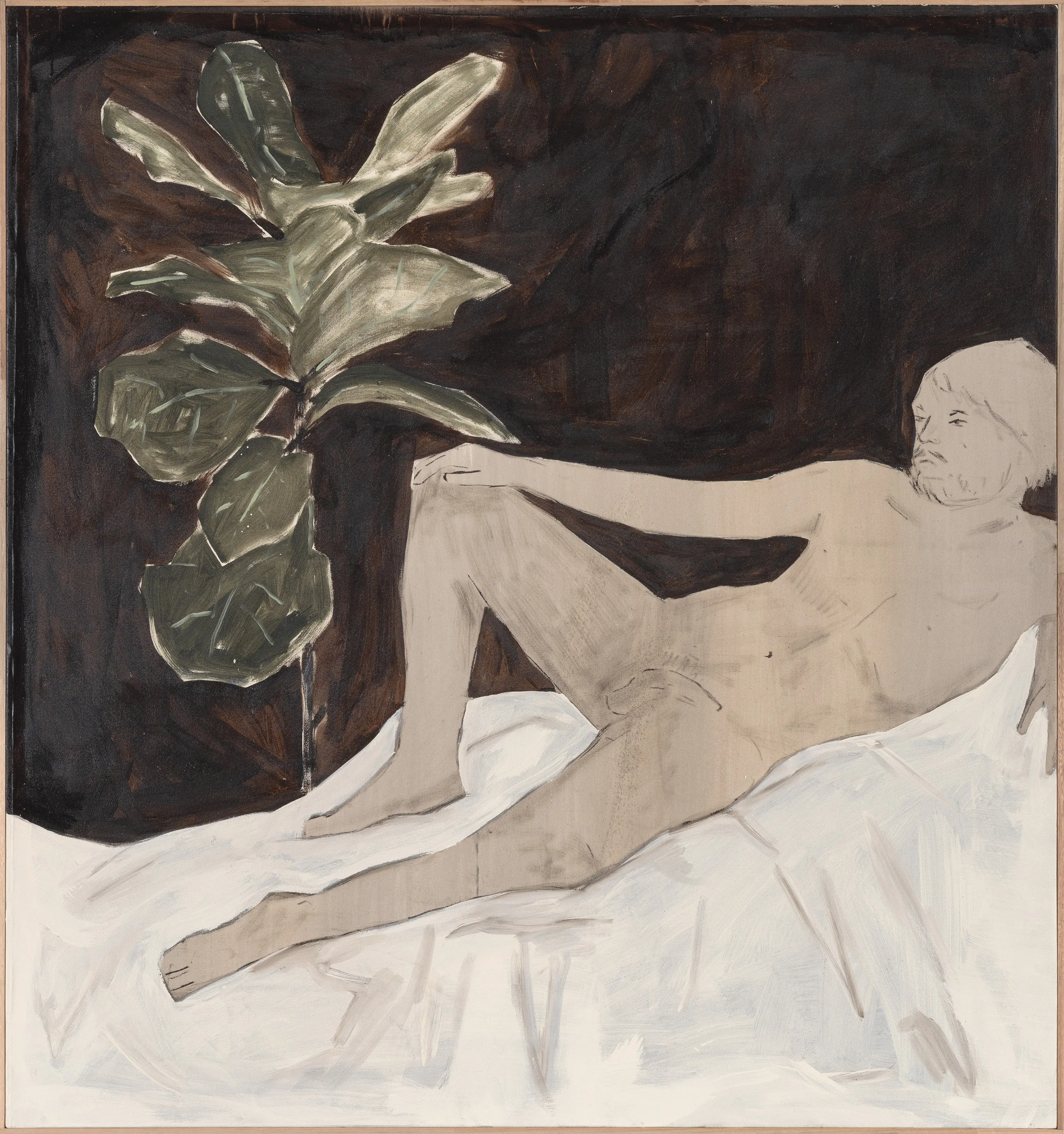

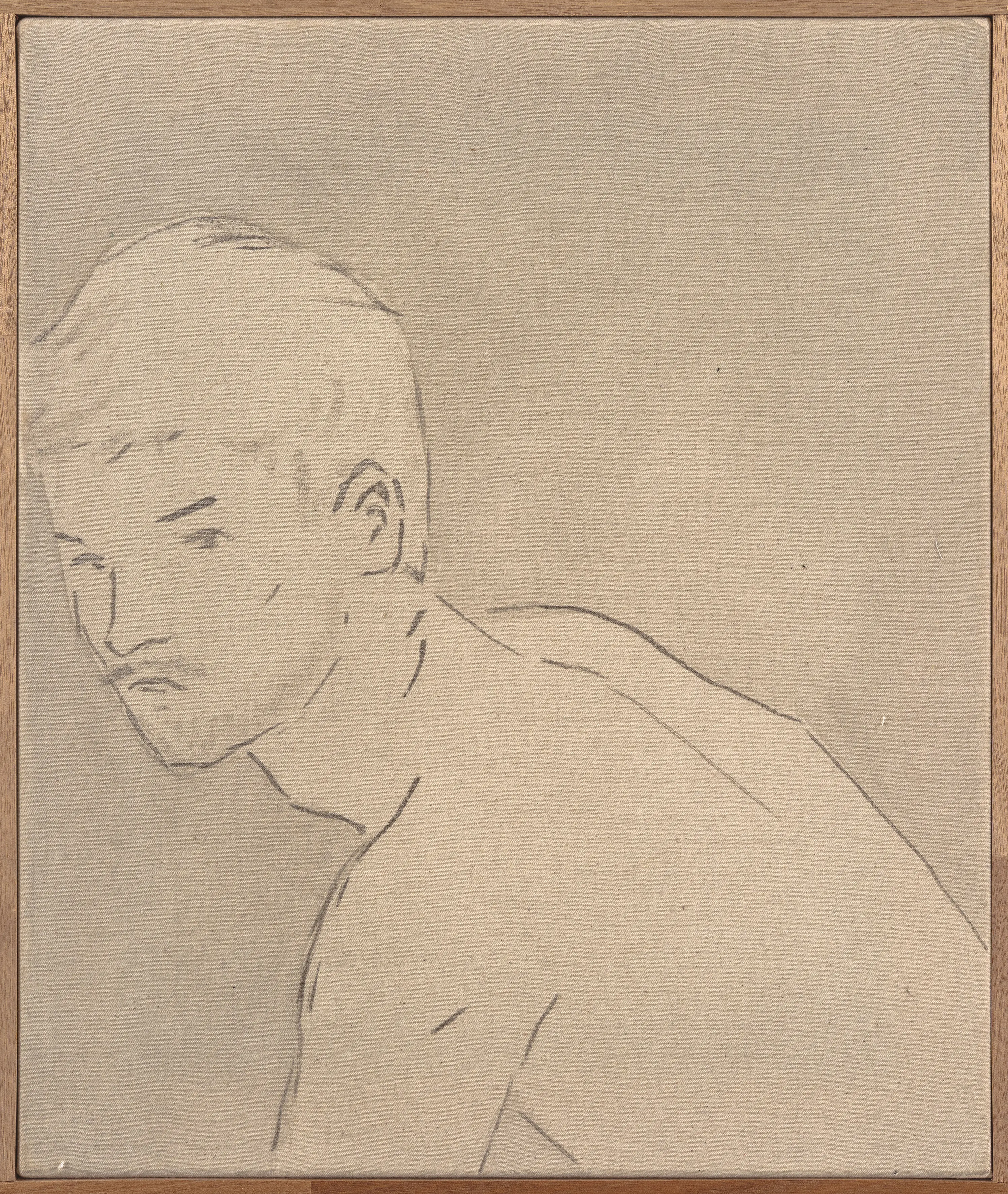

It's more like a design of the place and not necessarily about the people, I guess. It's about the situation of the painting. So not necessarily what they look like, but the dynamic between them or the things around them.

And have you always worked figuratively?

Actually, I didn't really do any figurative work before I graduated. I was more of an installation-type artist, doing text-based things, assemblages and so on. It probably became more figurative because I was getting more and more frustrated with not having much to say. I think it was also a question of money and what would be the easiest way to get my message across with something that I could hold or someone could keep. Painting became that for me. But I think it‘s also because I started to find and work with new materials such as bitumen.

What attracted you to these materials?

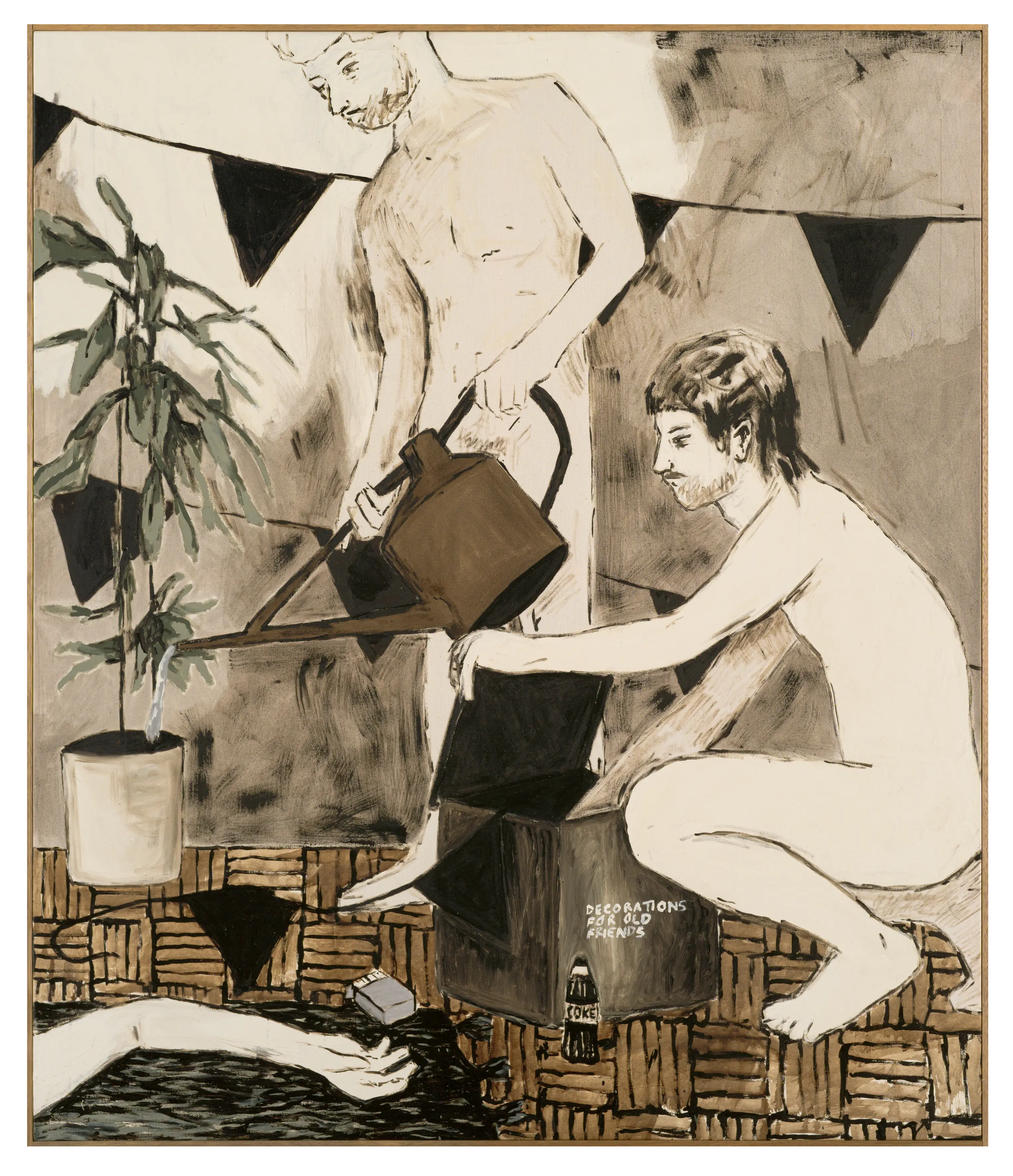

Well, again, it was a question of money. I didn‘t have a lot of money at the time, and bitumen is pretty cheap. At least cheaper than regular black acrylic paint. I actually bought it by mistake because it said "black" and I thought, oh, it‘s just paint. When it turned out to be bitumen, it was kind of a blessing in disguise. Bitumen has a sort of brown color to it, so I could sort of manipulate it to get black, brown and cream. I can mix it and get all these other colors. I started thinking about things like construction and men‘s work, and then it became this idea of questioning these fields with masculine connotations.

The color scheme also reminded me of old photographs. Were they a reference?

Definitely. In the beginning it was photos that I would find in old shops where people used to get rid of their shit. And I would find these pictures of sailor men and things like that, mostly in black and white or sepia. Painting them became a way of recreating and reimagining their stories and, I guess, in a way, creating queer narratives out of my imagination.

I think you were about 12 years old when Zimbabwe codified the laws criminalizing male same-sex intercourse. Were your parents supportive of your sexuality?

I was pretty lucky in that way. I mean, of course they cared, but I think it was more like, ugh, my son is just gay (laughs). So it kind of put me in the position of thinking maybe it doesn't matter.

Did this change in the law influence your decision to move to relatively liberal Cape Town?

Well, first of all I went to Johannesburg when I was 16 or 17. I dropped out of school and went to work. When that didn't work out, I went back to Zimbabwe and thought, no, I still can't live here, so I went to Cape Town to study.

At the Ruth Prowse School of Art, right?

Yes, at Ruth Prowse. So I started with graphic design. And... I mean, I was on the course for about two weeks and I thought, fuck no. Because I didn't want to be a graphic designer. So let me just do the next hard thing and be an artist.

In many interviews you’ve mentioned that the artist Felix Gonzalez Torres was a big influence on your artistic approach at art school...

Yes, his work really changed the way I looked at art. Before I was introduced to Felix Torres and art theory and the '90s and conceptualism and the AIDS epidemic and the work around it, I didn't really know anything about art. Looking back, that's probably what made me want to be an artist and changed my view of how to make work or how to see work.

I know that you did a lot of photography when you were a student. Can you tell me a little bit about your transition from photography to painting?

I think there's a lot more freedom in painting. For example, when I take a photograph I feel it's very much in your face, and when I paint it's much more emotional or spontaneous. You get more of a feeling or a mood out of a painting. There's more poetry in it, I think, whereas photography can be quite straightforward.

The balcony, where we have made ourselves comfortable on camping chairs, faces south and gets warmer as we talk. Brett once told me that he hates giving interviews. He'd rather talk about other people's work than his own. Not that you'd be able to tell from listening to him...

Your text-based work is influenced by poets such as Frank O'Hara, Eileen Myles, Joe Brainard and Allen Ginsberg. How do their texts intersect with the themes you explore in your paintings?

There are so many hidden things that I think about that end up in the paintings. A lot of times when I frame the paintings, I'll frame them with a cigarette or write notes around the frame, so there are things that are somehow related to those times as well.

So it's not like you're reading a poem and you're like, oh my god, I've got to make a painting out of this?

No, it's more about combining all that and playing with it. In a way, like an accumulation of post-gay liberation.

But how did this obsession with poetry come about? Did your parents read all the time?

No, they were quite simple people. We were farmers. So they were just like really working class people trying to make a living. I don‘t know how I got involved in it at all.

When I was researching your work, I read that Frank O'Hara died when he was run over by a dune buggy while sleeping on the beach at Fire Island.

It's weird, right? He also had this amazing lover who also wrote a lot of poetry. And he was really bad at spelling, so a lot of the poems you see of him have these spelling mistakes in them and they're quite beautiful. When I find them I'll send them to you.

Are you reading now?

I am.

Poetry?

Everything, really. I just finished this book of poems by Ocean Vuong.

I saw one interview you did with Cape Town TV where you were talking about a show you just did at the Goodman Gallery. You talked about this one piece and it was just a wooden book of Ginsberg's Howl.

Yeah, I really liked doing books at that time. Anything by Ginsberg I really like.

Right, I mean, the book is such a central element in all your work. I also remember seeing Susan Sontag's Notes on Camp in one of your works.

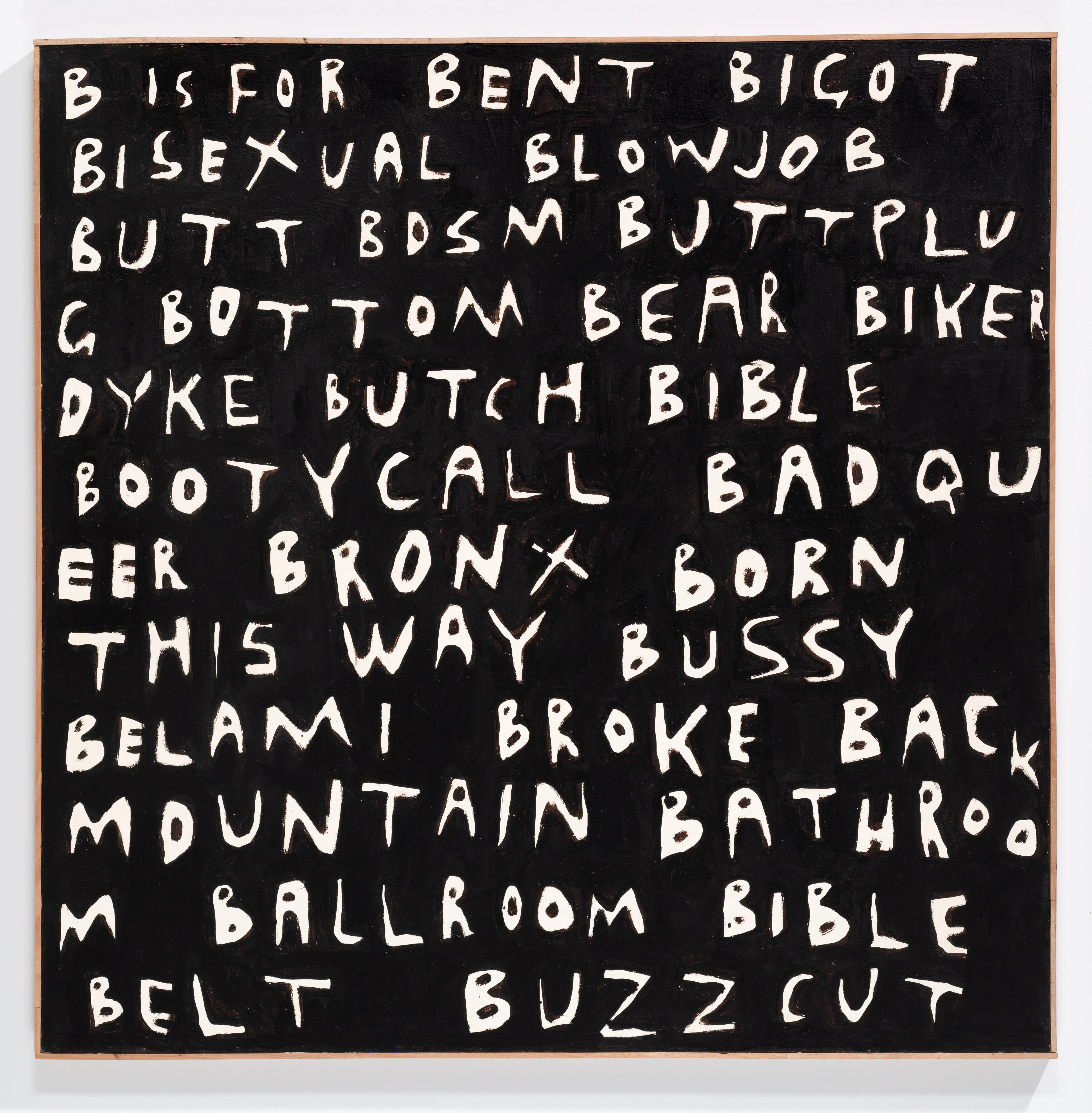

Susan Sontag has always been a big influence, I mean not just Notes on Camp but all her other work. Also the way she looks at photography. She really influences me and the way I look at my paintings. There's also a really nice quote from Zadie Smith that says camp is doing more than is necessary with less than you need. And a lot of times that's how I think about my practice: doing the most with the least I've got, like just my three colors that I use. So it's like doing everything I can to make a bigger statement than what it is.

Would you say that your work is camp?

I think it's quite campy. I find my work very funny and sad at the same time, which I find kind of campy. Because I find camp things really sad and embarrassing at the same time. I mean, it's definitely not camp in the sense that it's colorful (laughs).

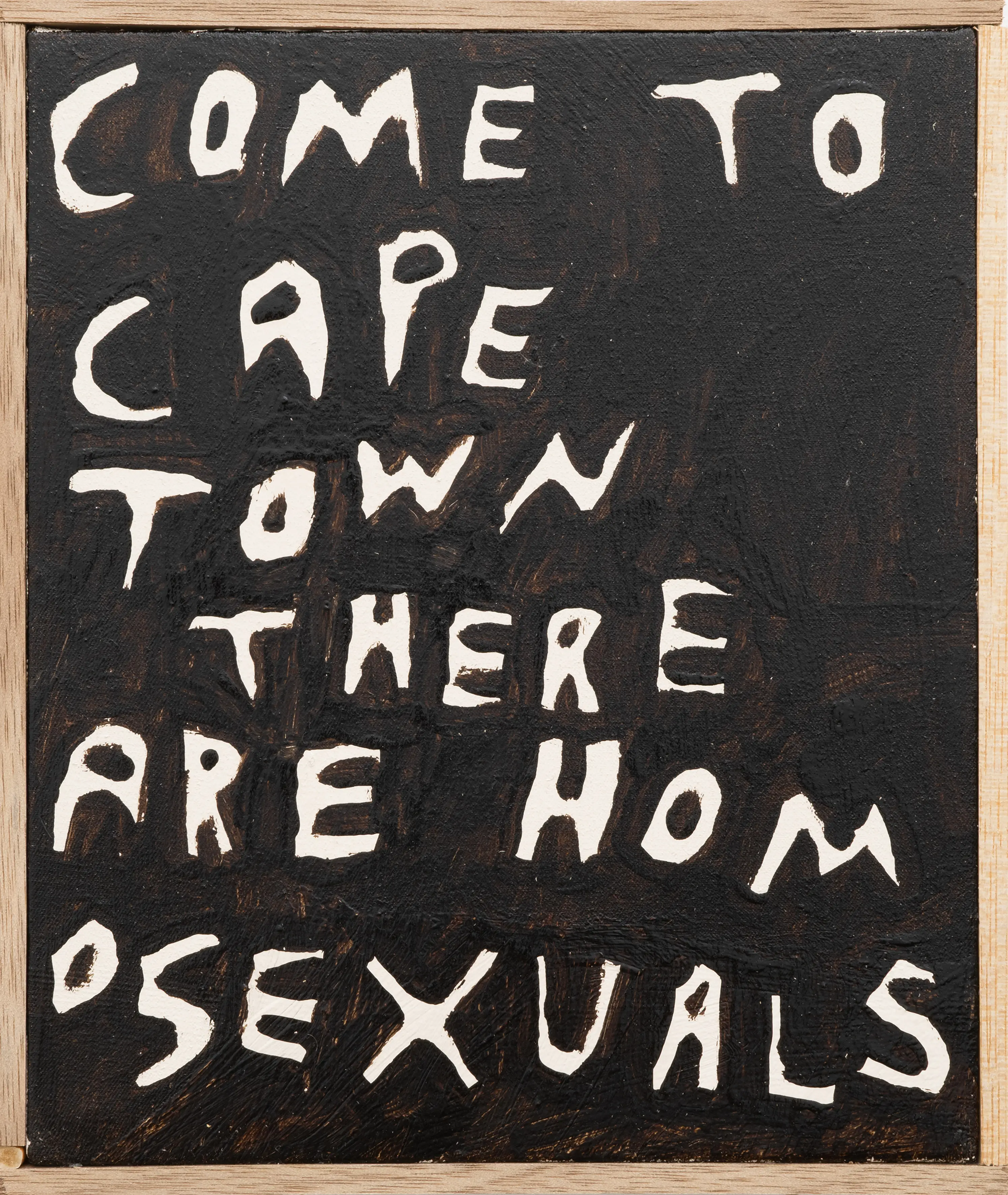

Sontag suggested that capturing the "fugitive sensibility" of camp requires annotation and list-making. Did this idea play a role when you made your Alphabet series?

There are quite a few artists in South Africa who have worked with the alphabet and I think maybe that's what kind of started it. But again, maybe a kind of Allen Ginsberg role of the tongue, so how many words can I come up with in this short amount of time? Sort of associating.

So there's no written script? It just goes straight onto the canvas?

It's always a spontaneous thing. I never write down what I'm going to paint. I just paint the canvas white and then write the text on the spot. So I have to have a canvas around in case it happens. And I think the sense of urgency is what makes them important. It has to happen now or it will go away.

If you Google Brett, you inevitably come across a German article in the Berliner Zeitung, the first sentence of which is infinitely corny but somehow also true, and which seems to me more and more like an accurate description as the conversation goes on: "A romantic has travelled from the Cape of Good Hope to Berlin with his paintings of scenes of tenderness."

When we first met, I remember asking you something about what it felt like to be an artist. And I remember that you were kind of irritated by the word "artist", as if you were not sure that you were one. How do you feel now?

That’s true (laughs), I think of myself more as an image maker or someone who makes things. I think the only time I really think I'm an artist is when there's an exhibition and I can see all my work together. But before that I'm just kind of stuck with all my paintings getting irritated by them.

Do you have a favorite piece of your art?

I think it always changes. I mean, sometimes I look at a painting and I think, yeah, it's a really nice painting, but it doesn't really mean that much to me. And then there are paintings that I really hate, but they mean a lot to me because I hate them.

What do you find most rewarding about being a painter?

Finishing the painting.

Getting the money (laughs)?

Sure, some monetary things (laughs). I guess it's mostly finishing a painting. Painting is a lot of troubleshooting and it's really satisfying when you get stuck on a painting and then you figure out how to make it work. And then you get your message across through it. And also when people relate to it, that makes me really happy.

What advice would you give to young and aspiring artists who are just starting out on their creative journey?

I don't know. Maybe don't drink beer. Or... drink a lot of beer (laughs).

I think we're done (laughs)...

What shall we do now? I would like to go to a lake...