Interview with Arturo Kameya

"Easy to Describe, but Not So Easy to Explain"

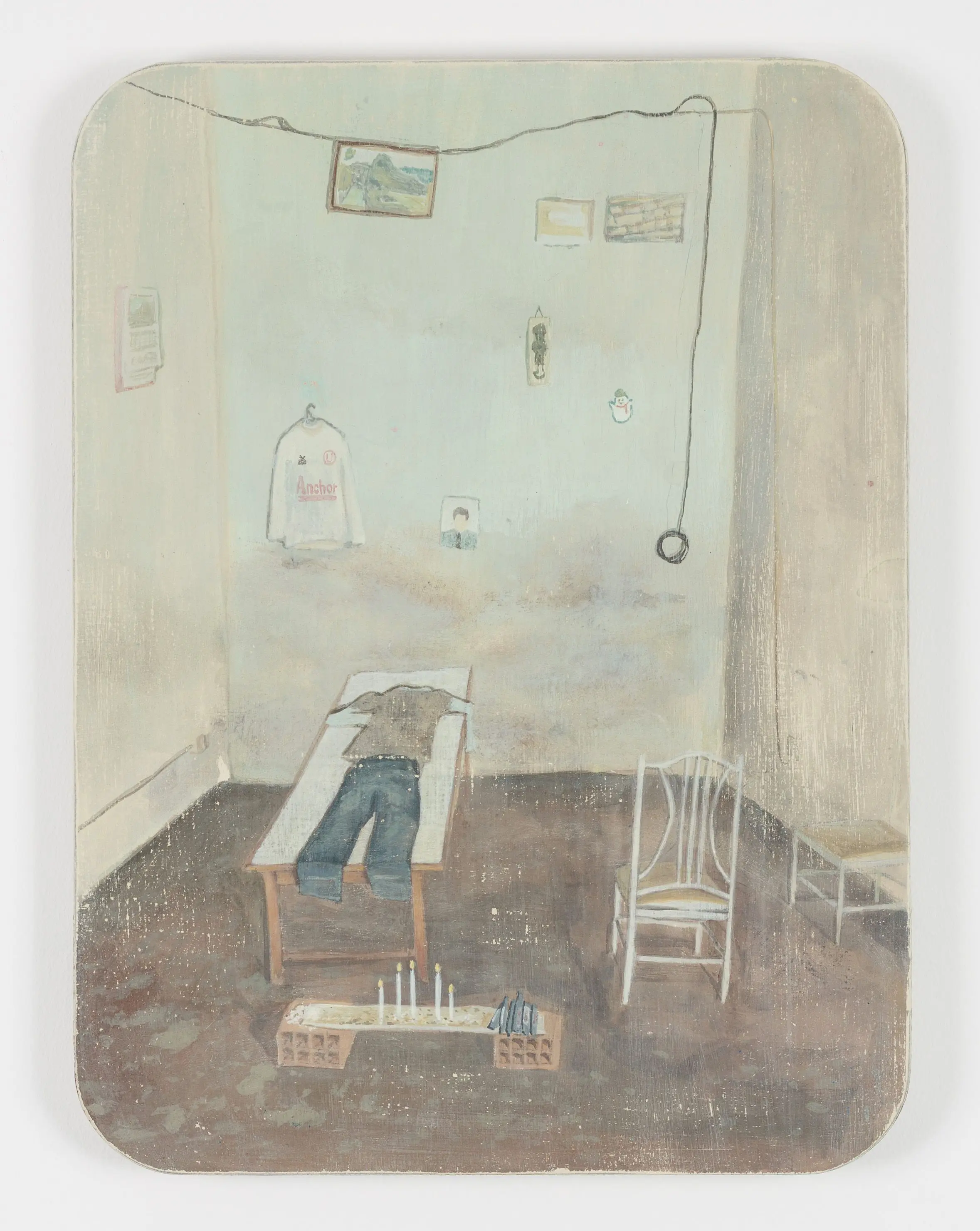

In vigilant depictions of his native country Peru, Arturo Kameya's magnetic visual language feeds on the individual and collective memories gleaned from the encounters and lived observations of growing up in Lima's urban middle class community. Challenging the pervasive Western formats of traditional modernism, the cultural and social realities of urban environments are sharply contextualized through the artist's intimate approach to material and form. In conversation with kennich, Kameya expands on the interlacing of art objects with the mythical motifs and textures of the everyday.

Your artistic practice is concerned with the narratives and myths that make up different versions of history. How do you navigate the complexities of storytelling and reinterpretation in your work?

Argentinian writer Enrique Dussel argues that myth is not an irrational explanation opposed to "logos", but a distinct type of rationality. It is a rationality that seeks to explain reality from multiple layers, including symbolic ones. The reason this is important is because it stands in opposition to a Hellenocentric self-perception where everything scientific is seen as civilization and everything else as barbarism. In this sense, the complexity doesn't lie in the descriptive aspect, but in the explanatory element.

From my point of view, a work of art is a series of decisions made by both the author and the spectator concerning tangible material. Therefore, I aim to make work that is easy to describe, but not so easy to explain. So, the complexity becomes a shared task with the spectator and the multiple layers of interpretation. On the other hand, there are many negative aspects to living in a time of hypervisibility culture; however, an advantageous one could be that now we can balance out hegemonic narratives in history writing with reports on microstories, whether they are meant to be reports or not.

Childhood memories, family traditions, and scenes from the suburbs of Lima stand at the beginning of your creative process. How does the endeavor of translating personal experience into art allow for a nuanced exploration of cultural identity?

Because cultural identity is not a straight line, it doesn't happen in an abstract dimension; it changes fast and is one of the first things to get flattened by the state when it becomes inconvenient. But for Latin American artists, there's a big distinction in the difficulties of doing work about identity between artists from the capitals and urban environments and artists from the countryside.

So, for example, in Peru, it is very easy to label an art show with false accusations and shut it down because it shows, not only, the nuances of cultural identity, as you mention, but also the power of history narratives. This has happened especially to artists from the countryside, who have experienced violence for decades, and on top of that, they have to bear the burden of a state that wants to keep them invisible. This is not the case for artists like myself, who came from the capital. We work from what we experienced, and often, what we've experienced is much easier, and we receive more opportunities. So, the exploration of cultural identity should include a reflection on which kind of privileges you are receiving as an agent of cultural production.

In 2021 you had an exhibition at the Dordrecht Museum in the Netherlands called "Drylands". The title of the exhibition suggested a certain aridity and stillness. How do you incorporate dynamic arrangements into your installations while maintaining the overarching theme?

"Drylands" was a show about the city of Lima, which is a city built on a desert valley. The title refers to the lack of resources and functioning structures, but it also refers to the activities that counter balance such aridity. So, it is not about a one-tune type of scenario but more about the actions and interactions within. This led to a series of works that focused on popular culture, systems of beliefs, ornaments, and micro identities. Therefore, it was planned as a series of paintings and installations that involved subtle movements and actions, most of them involving liquid. As in the case of the installation of the dog heads with foam coming out of their mouths that were placed on two metal structures similar to microphone stands, or the robotic fish, which was a soda can attached to some servo motors, that swims in a half-cut barrel of dirty water, and the ladder installation with a pump system that feeds a sculpture of a cat on top of the ladder dripping liquid from its nose onto the mouth of the ceramic cat at the bottom of said ladder.

Reading your interviews, you seem fascinated by the idea of cultural cannibalism. Could you elaborate on what this concept means to you in a contemporary context and how it influences your approach to materials and themes in your artwork?

The term cultural cannibalism refers to the movement initiated in Brazil during the 20th century, where Brazilian writers and artists sought cultural independence from the West. They referenced the resistance of the Tupí tribes and their anthropophagic practices as a metaphor to devour foreign cultural influences and then barfing something new from within. Decades later, artists like Hélio Oiticica would revisit these ideas. From my point of view, in contemporary times, this means nothing other than what occurs in reality; in popular culture, for example, where one sees daily occurrences in counterfeit products, music, fashion, and so on. It is also a much faster channel than the academic world because, unlike the latter, the former does not dwell on the abstraction of each issue raised, but resolves it without the skepticism of academia. Analysts will take care of the results.

Your exploration of an object's provenance, which you call "material afterlife," raises questions about the evolving meaning of cultural artifacts. How do you see this concept influencing the broader dialogue around the preservation and display of cultural heritage?

The way I see it, there are multiple layers on top of the tangible material, and there's only a limited number of artifacts in the collections. One can argue that there will always be new findings, but I found not much difference in the curatorial logic behind an ethnographic museum and the Rodin Museum, for example. Rodin made a number of works, and there won't be much else there to discover, yet the shows in the museum keep producing new content, even when they use the same matter to convey new meanings. The difference lies in that there's no place for Rodin's pieces to return to. They belong where they are. The material afterlife, in the case of material culture museums, depends not on the abstraction of the ideas upon them, but on the tangible politics and the relationship between countries and institutions.

The use of the term "ghosts" to describe museum objects introduces a dimension of spirituality. How do you perceive the relationship between the tangible and intangible qualities of objects, and how does this influence your artistic choices?

One aspect museums are trying to leave out of their internal politics is an object's spirituality and ritualistic elements. The reason is clear: How would they really know what it means and what it meant for a culture outside their context, an object that is now displayed in the museum? Therefore, they are trying to be "respectful" to the object and the culture of origin by only dealing with the tangible information about it. Yet, a lot of these objects didn't have a purpose outside a specific ritual, place, or intangible function.

Of course, one has to be skeptical about the real reasons for this approach. Since we are constantly subjected to a judicial logic in which everything will be judged, museums are the first to take a more cautious strategy to display objects. In that process, they end up leaving out key aspects of a large percentage of their collections to not open the door to the claims for the objects to be returned. When I first came to the Netherlands, I did some work based on this dichotomy, but I soon realized that until these collections return to their origin, most discussions about the intangible qualities of these objects become futile.

Given the ethical questions you've raised about the existence of ethnographic museums, how do you see the role of art in navigating and engaging with these ethical concerns? What potential does art have to reshape the discourse surrounding the display of cultural artifacts?

I think the world will eventually turn these reflections on the existence of such museums into demands for them to take action on these discussions with a more substantial leverage. And not leave them in a dialectical dimension. Art is not a separate agent of the world. It also moves around tendencies.